A laboratory in your hands!

Smartphones have come a long way in the last decade. They only used to do one thing back in the day — Phonecalls. Now, they do a lot more than just allow you to speak to someone. It is a mini-laboratory with which you can perform lots of experiments and understand a lot about the things around you.

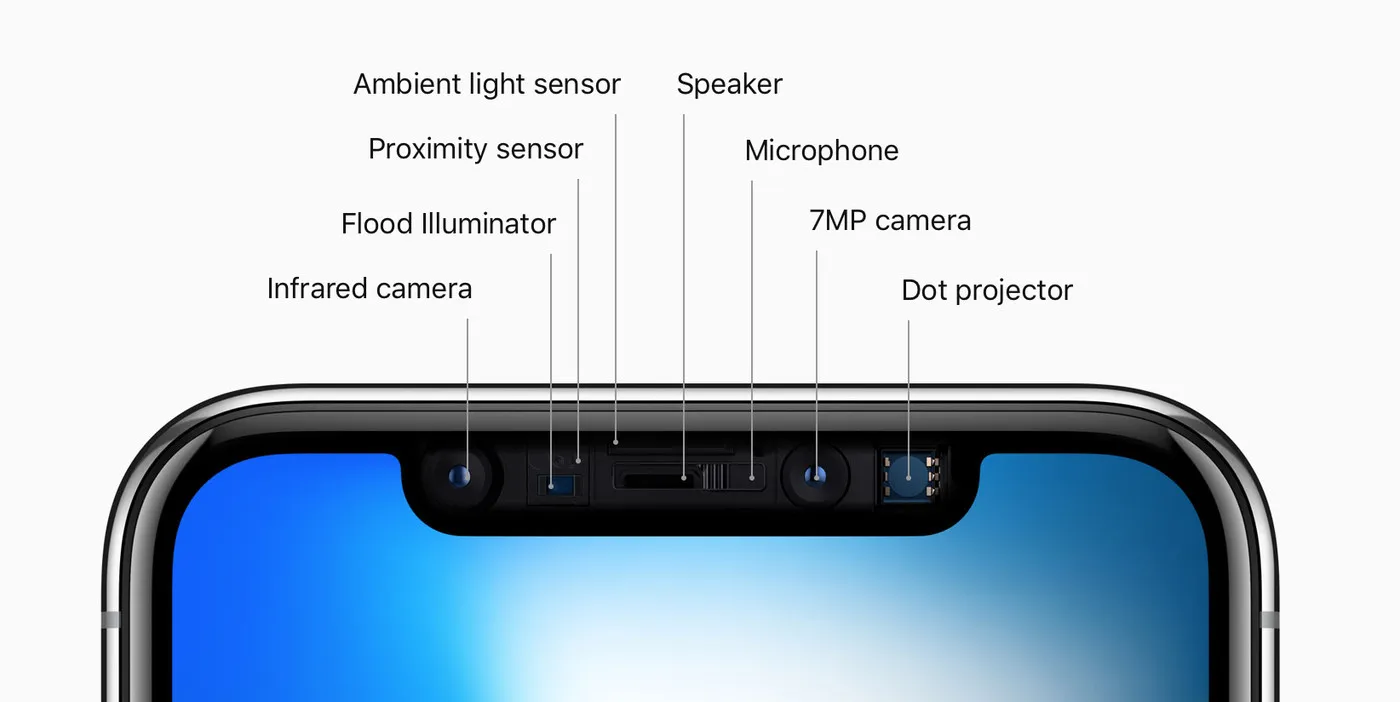

When the iPhone X came out 5 years ago, there were mixed reactions. A lot of people did not like that the whole screen wasn’t usable and that there was a weird-shaped notch. But there was a reason Apple needed that notch. They needed space to put a bunch of sensors underneath the screen. You can see in the image below just how many sensors are in that small area.

Now, If you think those are a lot of sensors, then you’re in for a surprise. Every phone that we use today has a lot more sensors underneath the casing. They are used by the apps on your phone to do various stuff. Ever used apps that count the number of steps you have taken in a day? They all use a sensor on the phone to get that data.

You do not need to be a Software engineer or an App developer to access that data. Google, a while ago launched an app to get people interested in sensors and electronics. This app has now been taken over by Arduino. With the help of this app, you can log all the data coming out of your phone’s sensors. When I first discovered this, I went nuts and performed all kinds of experiments using my newfound laboratory. I will show a few of my experiments here in this small tutorial. We will see how to use those sensors to understand a few things around us. My goal through this article is to inspire you to perform basic science experiments on your own and discover new stuff. All you need is a smartphone ( Android or iOS based) and the Science journal app to get started. You can find the links to these apps below. So let’s begin!

Link to download the app for Android phones

Link to download the app for Android phones

An Elevator joy ride

I stay in a building that has 30 floors and one day, when I was in the elevator, I realized that my ears felt weird when I was going up and down. This is something you feel in an airplane too. Now, I know this is due to the pressure difference between different floors but I wanted to see exactly how much pressure drops. Out comes my mini lab.

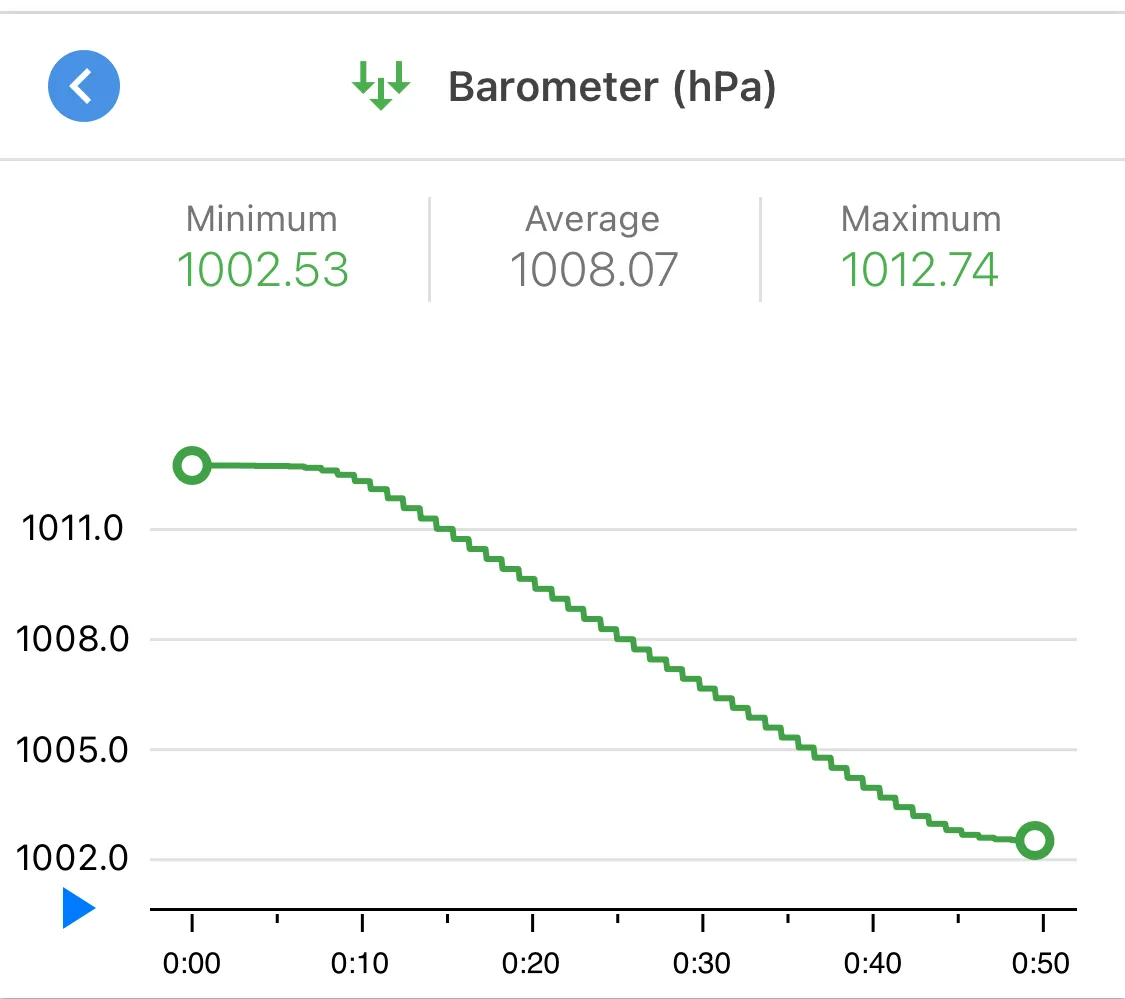

This data was collected in an elevator traveling from the basement to the 30th floor. The pressure is shown here in hectopascals (hPa) which is equivalent to millibars. So, going forward, I will use millibars as the units for pressure. I stay right by the sea so the maximum pressure you see here — 1012.74 millibar is the sea-level atmospheric pressure. Each step in the picture indicates the elevator crossing a floor. If you count those steps, you will see that there are 33 of them indicating that the pressure dropped 31 times. From the basement of my building to the 30th floor, the pressure has dropped about 10 millibars. That might not be much but is enough for your ears to sense the difference.

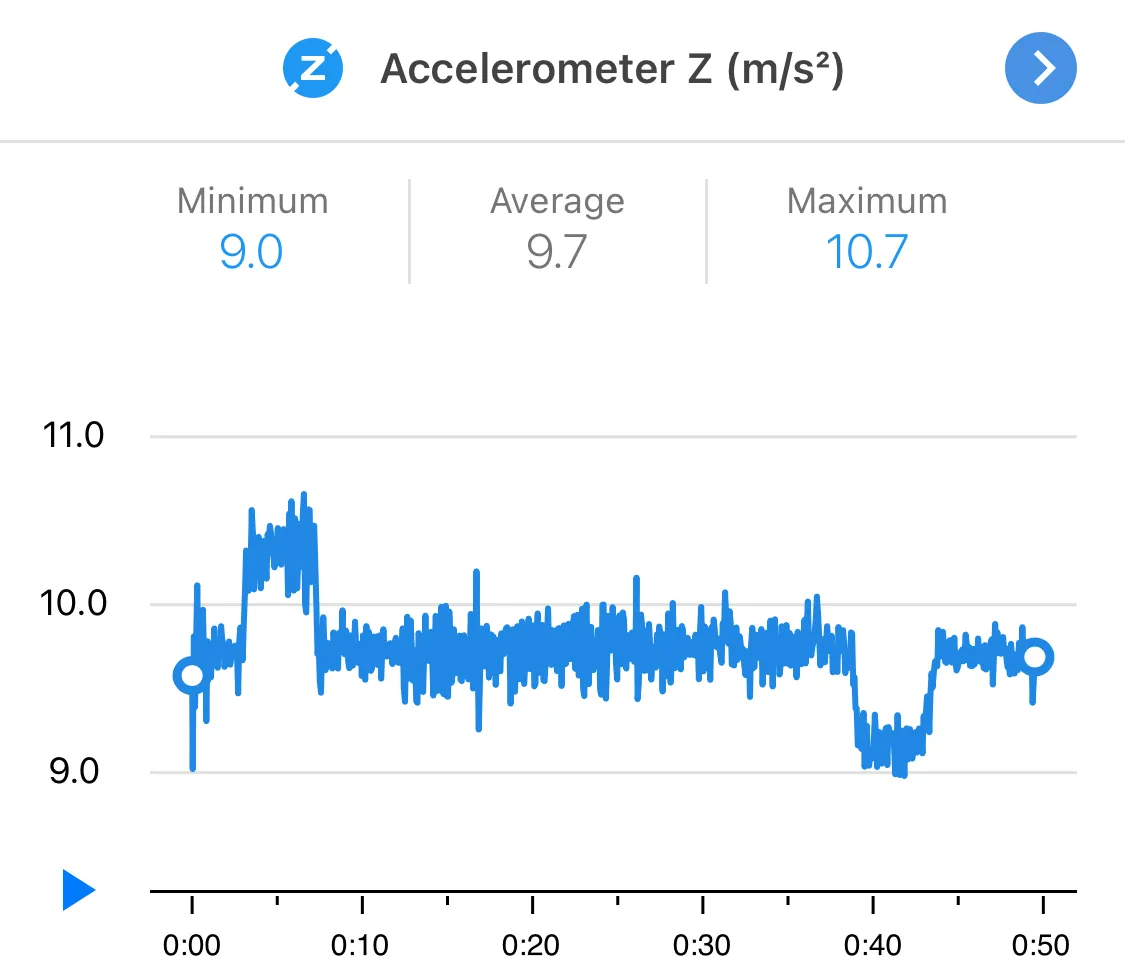

The accelerometer, which is a type of sensor that calculates acceleration, can be used to get an idea of the forces acting on you. We are all familiar with the term G-force, a term frequently used by pilots to indicate just how much force they experience during flight. G force is the amount of force gravity exerts on you. 1G = 9.8 m/s² and you can see from the image below that the average acceleration shown by the sensor is 9.7 m/s² which is pretty accurate! The two peaks shown in the image below, one rising and one falling indicate when the elevator starts and stops respectively. They indicate opposite forces.

A laboratory up in the air

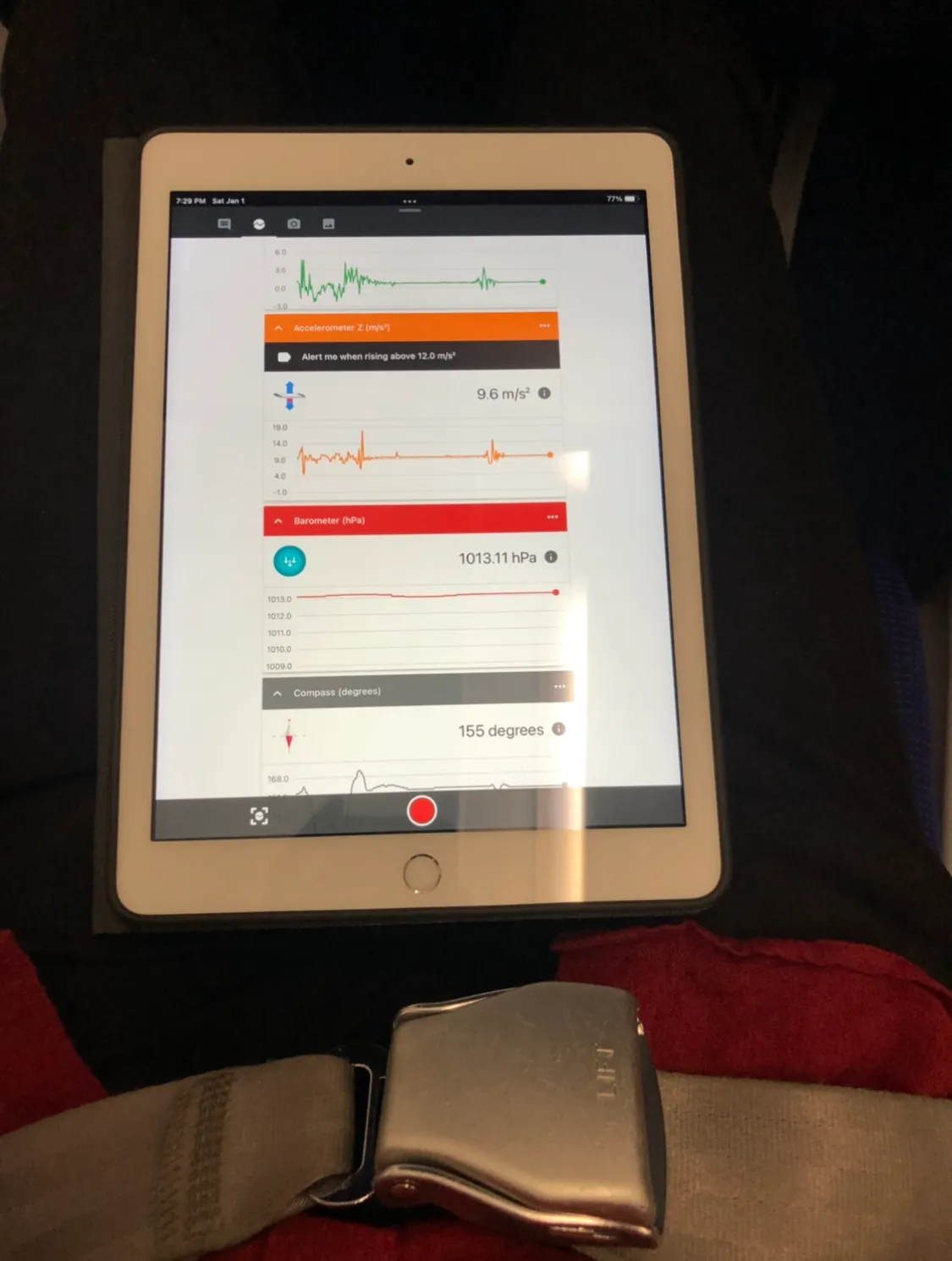

One other area where you can do a lot of experiments is when you’re on a flight. Remember your ears popping every time you take a flight? That is again due to the rise/drop of atmospheric pressure. Using the accelerometers and the barometer on our phones, we’ll learn a few things going on during the flight. I used my iPad to log all the sensor data during a short flight. Keeping my legs absolutely still for an hour and a half to keep the sensor data from getting corrupted was difficult, to say the least, but in the end, was worth it!

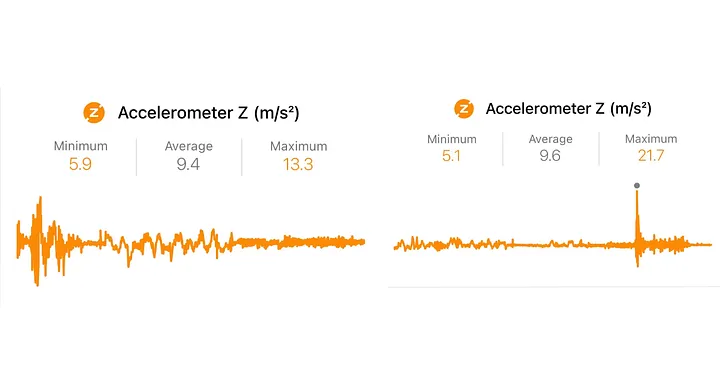

I have logged the accelerometer data on all three axes (x, y, and z), the barometer. As you can see in the image below, the z-axis accelerometer data shows the force acting on you throughout the flight. The left side shows the data during takeoff and the right side shows the data during landing. Except for the takeoff and landing phases, the flight was relatively smooth. Things to note here are the G forces during those phases. The takeoff was smooth and the maximum G force was about 1.5G. Landing, on the other hand, was quite dramatic as you can see from the data below. The peak G force was about 3.5G during that phase. Glad I had my seatbelt on!

The gray dot you see in the image below is an indication that the G force exceeded 3G. I had set a trigger to indicate visually that the G force exceeded a certain limit (3G in this case).

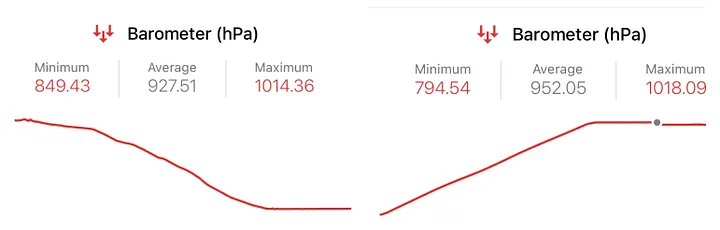

The barometer readings provide an interesting picture too. The image below shows the pressure drop and rise as we gain and lose altitude. Note that the maximum pressure on the left is 1014.36 which is the sea level pressure (I was flying out of Chennai). The aircraft eventually reached an altitude of 25000 feet. Now, using this website you can calculate the pressure at that altitude. So, at 25000 feet comes to about 375 hPa. The pressure inside the cabin doesn’t get anywhere near that as we wouldn’t be able to survive at those levels. The aircraft’s climate control keeps the internal pressure at about 950 hPa on average which is like being at an altitude of 1700 feet.

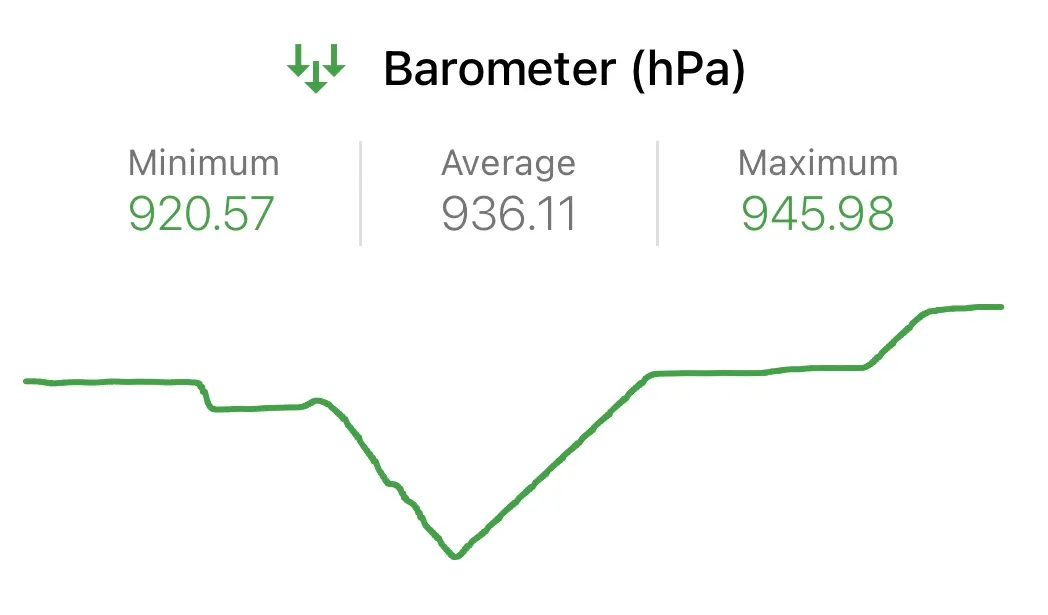

The aircraft’s climate control system can be seen in action. Now I could not really see the control system make corrective changes on the Airbus A320 but I captured the barometer readings on a smaller aircraft (A turboprop ATR 72) with a much slower control system that showed how the system reacted to the drops in the cabin pressure. In the image below, you can see that the cabin pressure started out at 920.57 hPa and then started dropping rapidly indicating a rise in altitude. But then you see the cabin pressure start to increase. This is the aircraft’s climate control taking over and restoring comfortable pressure levels inside the cabin.

A few experiments on my own body

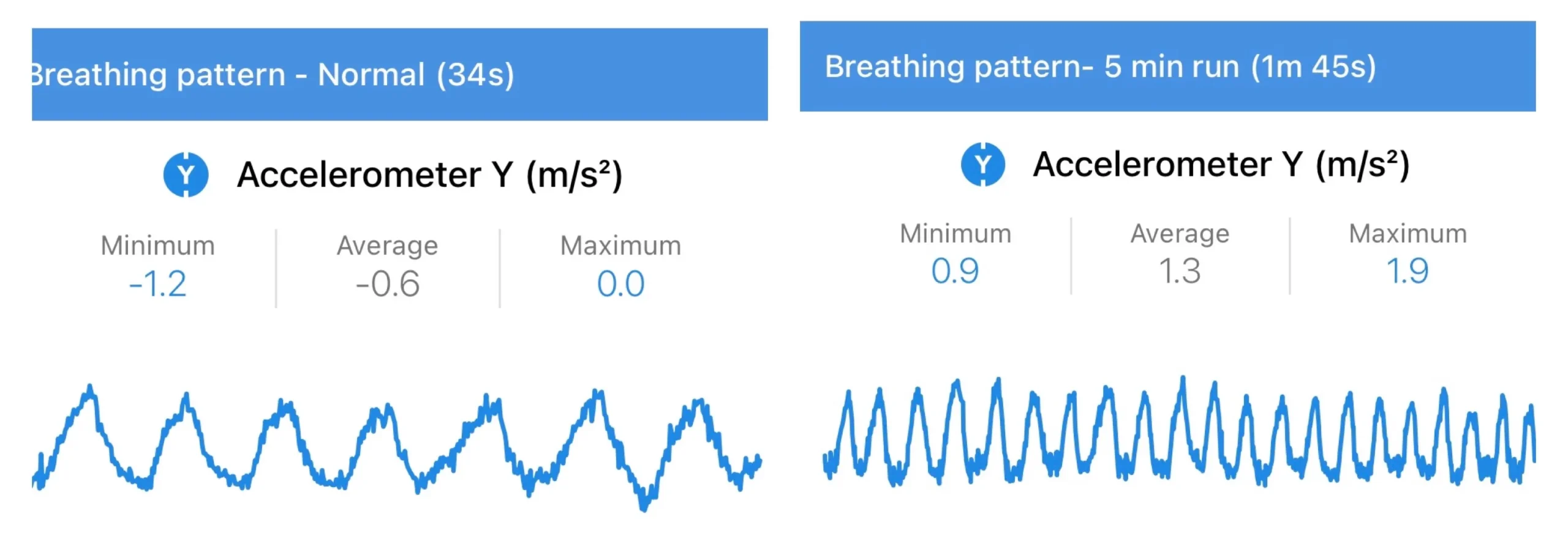

Lastly, you can also use your phone to perform a few experiments on your own body. All you need for this set of experiments is the accelerometer readings. If there is any force acting on the phone, the accelerometer picks it up. Here, the force is applied by my chest going up and down as I breathe in and out. I placed my phone on my chest with the Y-axis accelerometer set to log data. The axis used to measure can be picked based on whether you are lying down or standing. What you see below is my normal breathing rate and the rate after a 5-minute workout. See how fast I breathe after some exercise?

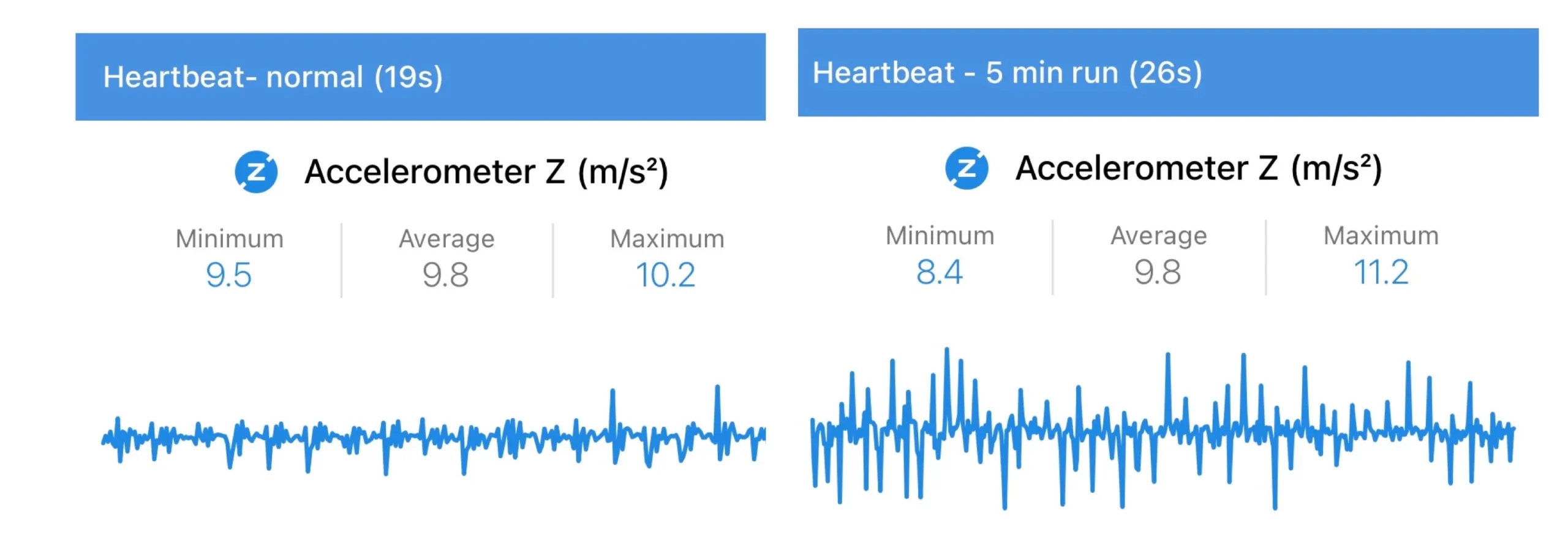

The accelerometer data can also be used to check your heartbeat. The Z-Axis data was used to measure the heart rate. Each peak you see in the images below corresponds to one heartbeat. The image on the left indicates a normal resting heartbeat and the one on the right indicates my heartbeat after a five-minute workout. The pronounced peaks on the right show how hard my heart is working after a small workout.

That is all for now folks! In the future, I’ll be updating this article with more experiments. Next time I take a roller coaster ride, I will be at work. This app in many ways has changed how I see surroundings. Now, every time I go outside, all I think about is how to use the sensors I’ve got in hand to perform a few experiments and discover something new. Hopefully, with this little article, I have inspired you too to be curious. Have fun!

You can also follow me on hackster to see more interesting projects. I’ve got a fun little series of tutorials there where I break open an internet router and change its software.